Icing and FIKI

Objective

To understand the formation, dangers, and mitigation of in-flight icing and how to avoid it.

Timing

30 minutes

Format

Overview

- What is icing?

- Hazards of icing

- When does icing form?

- Kinds of icing

- Accumulation rates

- Ground icing

- Icing weather products

- Icing in and around thunderstorms

- Ice accumulation playbook

- Flight into known icing certification (FIKI)

Elements

What is icing?

Aircraft icing is ice that accumulates on the structure or in the induction system and is associated with a variety of hazards.

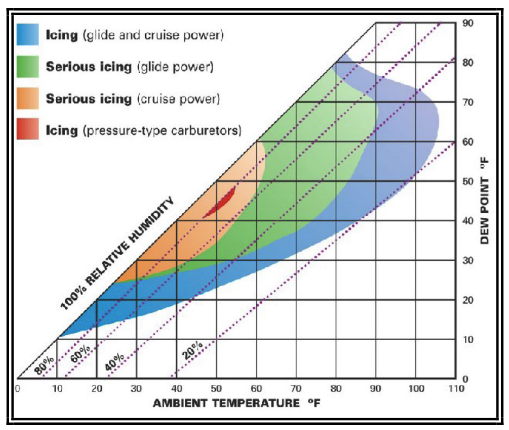

Induction system icing (e.g. carburetor ice)

- Carburetor ice occurs due to the effect of fuel vaporization and the decrease in air pressure in the venturi, which causes a sharp temperature drop in the carburetor.

- If water vapor in the air condenses when the carburetor temperature is at or below freezing, ice may form on internal surfaces of the carburetor, including the throttle valve.

- Carburetor ice is most likely to occur when temperatures are below 70°F (°F) and the relative humidity is above 80%.

- Due to the sudden cooling that takes place in the carburetor, icing can occur even in outside air temperatures as high as 100°F and humidity as low as 50%.

Structural icing: Ice that forms on the airplane's exterior structure

- Ice tends to form on small or narrow objects

- Types of structural icing

- Rime ice: Rough, milkly, opaque ice

- Forms by instantaneous or rapid freezing of super-cooled droplets as they strike the aircraft's surface

- Formed by lower temperatures, smaller amounts of water, and smaller droplets

- Clear ice: Slow accumulation causes smooth, clear, "glazey" ice to form

- Formed by larger amounts of water, high aircraft speed, and large droplets

- Water melts and "runs back" along the wing before it freezes. This can be out-of-reach of you de-icing system

- Typically more dangerous that rime ice

- Mixed ice: A combination of clear and rime ice

- Rime ice: Rough, milkly, opaque ice

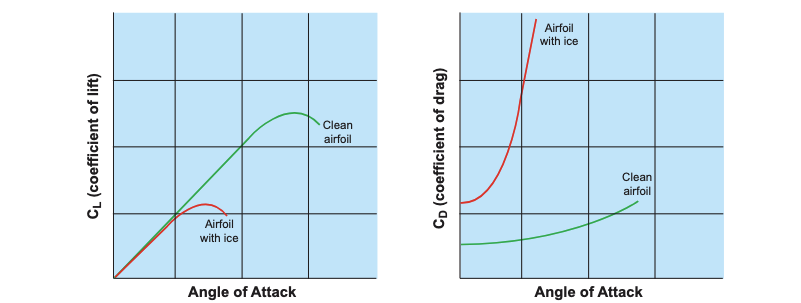

Hazards of Structural Icing

- Ice alters the shape of an airfoil, reducing the AOA at which the aircraft stalls

- Note: This may have no effect in cruise but pose a significant risk during approach and landing

- Ice can partially block or limit control surfaces, making movement ineffective

- Ice also increase aircraft weight

- Roll upset can occur with self-deflection of the aileron

- Ice-Contaminated Tailplane Stall (ICTS)

- Since the horizontal stab is thinner than the main wing, it will accumulate ice quicker

- A tailplane stall can occur when the tailplane exceeds its negative AoA, often after deploying flaps

- This causes the nose to drop

- Be on the lookout for: Sudden changes in elevator effectiveness, force, trim changes, pulsing, osilications or vibrations

- If you suspect a tailplane stall:

- Retract the flaps, if lowered

- Add power and use previous airspeed/attitude combination which gave you S&L flight

- Propeller icing

- Ice tends to form on the spinner and inner radius of the propeller

- This results in a loss of thrust as the propeller is less aerodynamically efficient

- Other icing

- Windshield icing: May severely limit forward visibility

- Stall warning systems: May become immovable (for instance the AoA indicator on a Cirrus)

- Antenna icing: Antennas that do not lay flush with the aircraft’s skin tend to accumulate ice rapidly

- Radio reception may become distorted

- Antennas can also break off with enough ice accumulation

Factors Which Affect Ice Accumulation

- Water content

- Temperature

- Droplet size

- Aircraft design

- Airspeed

PIREP Accumulation rates (AIM 7-1-19)

- Trace: Ice becomes noticeable. The rate of accumulation is slightly greater than the rate of sublimation

- Light: Occasional requires manual activation of the deicing systems. May become hazardous after an hour in the icing conditions

- Moderate: Requires continuous use of the deice system

- Severe: Conditions where the deice system fails to remove ice and accumulates in places normally not prone to icing

Ground Icing: Frost

- Frost may form overnight when the temperature is below freezing and dew forms on the wings

- Just like airframe ice, this can have a significant effect of the aerodynamics of the airfoil and adds weight to the airplane

- Any accumulation of ice or frost should be removed before attempting flight

- How to remove frost: Rag with deicing fluid, deicing fluid spray, or a light brush

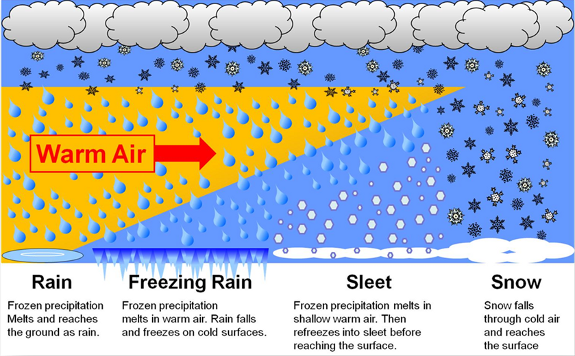

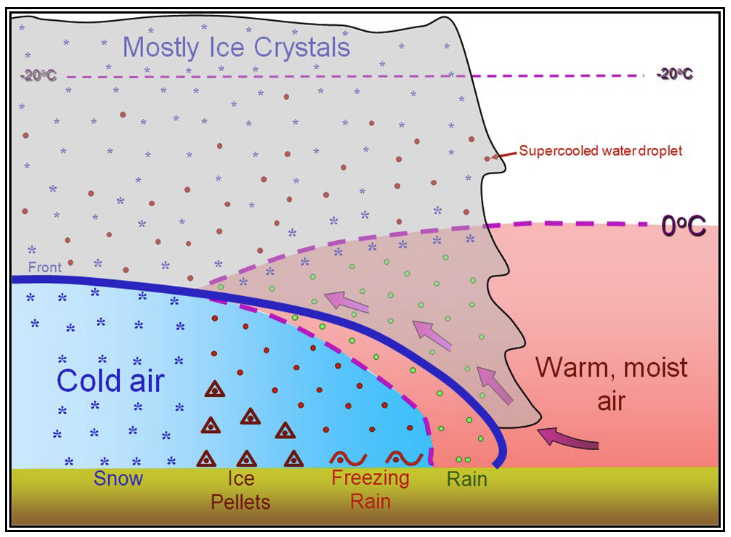

Conditions Which Form Ice

- There is potential for icing anytime you're in visible moisture and the temperature is near or below freezing

- Most ice forms between -20° and 0°

- About half of reports are between -8 °C and -12 °C, and between 5,000 and 13,000 ft.

- Cumulus clouds and thunderstorms

- Ice can form in all levels of a cumulus cloud

- Updrafts make SLDs and cold temperatures in the upper levels of a cumulus

- Strataform clouds:

- Generally trace to light

- Often you can climb/descend out of the cloud, or descend to warmer air

- Freezing rain: Severe ice can accumulate extremely quickly

- Warm fronts can create the potential for freezing rain and supercooled large droplets (SLD)

- Freezing fog

Icing Weather Products

- Freezing level chart

- AIRMETs: Moderate icing and low freezing levels

- SIGMETs: Severe icing

Ice Accumulation Playbook

- Pitot heat ON

- Ice protection system (TKS, boots) ON

- Windshielf defrost: ON

- Determine course out of icing conditions (climb, descend, turn)

- Aircraft-specific inadvertent icing encounter checklist

Removal of aircraft ice in flight

- Ice will sublimate after moving to clear air, but this can be very slow

- Ice will melt if moving to warmer air

Landing with accumulated ice

- Be very caution of configuration changes, particularly flaps. Deploy flaps in stages

- Perform a reduced-flap landing on a long runway, if possible

- Carry a higher-than-normal power setting into the approach

- Refer to the POH/AFM for approach airspeed with ice

- Increase approach airspeed by at least 25 percent above non-icing airspeed for the applicable flap setting

Icing regulations: 91.527

- "No pilot may take off an airplane that has frost, ice, or snow adhering to any propeller, windshield, stabilizing or control surface; to a powerplant installation; or to an airspeed, altimeter, rate of climb, or flight attitude instrument system or wing"

- No pilot may fly under IFR into known or forecast light or moderate icing conditions, or under IFR into known light or moderate icing conditions, unless the aircraft is FIKI-certified.

Flight into known icing certification (FIKI)

- "Flight into known icing": Any flight conditions where you’d expect the possibility of ice forming or adhering to the aircraft based on all available preflight information

- FIKI is a certification process that occurs when the aircraft is developed

- Is you aircraft FIKI certified?

- How to tell: AFM or POH references "part 25 appendix C"

- If your A/C has a MEL which includes icing conditions

- Features of a FIKI airplane

- Pitot-heat: Hotter than a no-FIKI model

- Carburetor heat/Alternate air

- Windshield defroster or anti-ice panel

- Wing boots or "weeping wing"/TKS system

- Propeller anti-ice system

- Stall warning system heat

- Fluid quantity gauge (weeping wing system)

- Note some aircraft have the above features but our not FIKI-certified, like our SR22

- Note: Even airplanes approved for flight into known icing conditions should not fly into severe icing, freezing rain or freezing drizzle.

References

- 91.527

- Instrument Flying Handbook pg. 4-13

- AIM 7-1-19: PIREPs Relating to Airframe Icing

- AIM 7-1: Icing Weather Products

- AIM 7-6-15: Operations in Ground Icing Conditions

- Aviation Weather Handbook pg. 20-2

- AC 91-74B

- Article about FIKI

- NASA Icing Course